The coupling of coincidence and choice

The things that make our lives are so tenuous, so unlikely, that we barely come into being, barely meet the people we’re meant to love, barely find our way in the woods, barely survive catastrophe every day…Trace it far enough and this very moment in your life becomes a rare species, the result of a strange evolution, a butterfly that should already be extinct and survives by the inexplicabilities we call coincidence. The word is often used to mean the accidental but literally means to fall together. The pattern of our lives come from those things that do not drift apart but move together for a little while, like dancers. They come together in these moments that are the coupling of unseen forces, a generative warmth, a secret romance between the unknowns that are also our parents. — Rebecca Solnit

When I started my marathon journey blog, I wrote early on about an observation by Eric Meyer, whose young daughter had passed away. He remarked that after such catastrophes sometimes couples split up, but there is no formula or calculus to know which couples will make it and which won’t. “It isn’t strength that keeps a couple together in the face of crisis. It’s having the luck to remain compatible under the most extreme pressures,” he said. “Like any complex interaction between two complex systems, the outcome is fundamentally unpredictable.” It has to do with the series of moments of coincidence that make up the couple’s history and experience.

Not all the accidents in our lives that provide the things that fall together to make us are secret romances and warmth. Some of the accidents are catastrophes, misfortunes, and several are moments of decision, a moment to change everything and end a marriage, quit one’s job, or move across country. Those moments of decision are patterns and have a regularity, but they are also the results of all the things that barely happened to put us there, at that moment of decision. As Meyer and Solnit note, even these dramatic accidents are not alone sufficient to move a life in one way or another. There is always agency, always a series of moments of decision that give movement to those inexplicable coincidences.

During the process of my separation and divorce a supportive friend once told me her marriage was in shambles and she had been thinking of leaving for a long time, but either she didn’t have the courage or hadn’t yet arrived at the moment of decision to leave. She wasn’t sure why she hadn’t arrived there yet, because she was truly miserable. But the inexplicabilities of her life’s coincidences had taken her to a place that was not her moment of decision. For couples who do split up, the series of accidents and whether and when they lead to a split or not are ultimately unpredictable; frequently friends remark with surprise because the couple in question was one they thought would always hold together.

There is often nothing grand or dramatic or even particularly clear about the arrival of that moment in a marriage; it most often doesn’t arrive with fanfare or drama. Sometimes it arrives because of the accidents of catastrophes and misfortunes and other dramatic moments, but whether or not such catastrophes lead to a moment of decision and what direction that decision takes are fundamentally unpredictable. Rather, they contribute to the coupling of unseen forces of things that did not drift apart, but moved together for a while until that moment of decision was taken up.

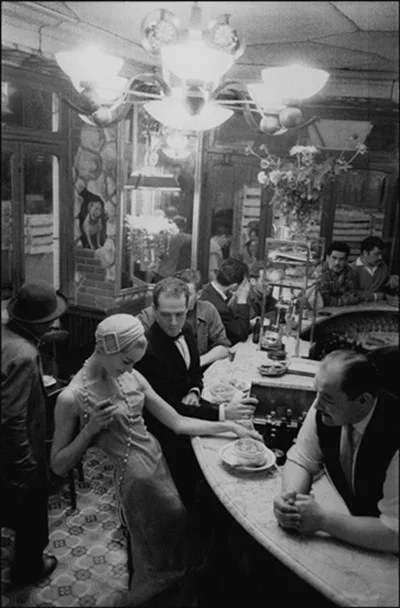

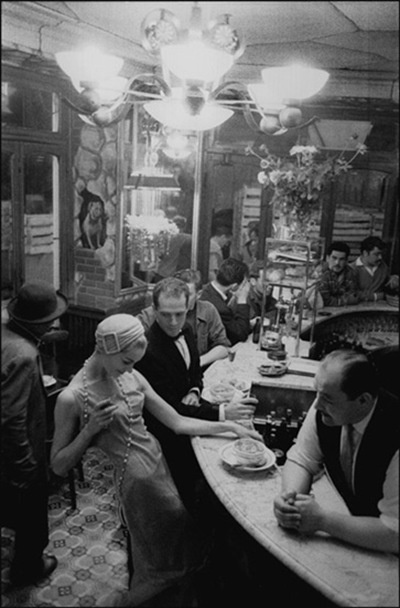

Like other incredible events, the exquisite candid and fashion photographs of Frank Horvat often came about because of a coupling of unseen forces, patterns of moments that suddenly coalesced and made manifest a particular moment in time. Horvat’s trick was to carry a camera at all times, so he could increase his chances of capturing such inexplicable coincidences. Building a writing practice or a new career or a new love are all a coupling of coincidence and choice, combined with a decision to carry that camera.

We Americans in particular have a love-hate relationship with the deus ex machina of the story. Like the ancient Greek critics, we prefer for events to unfold neatly based on the statistical evidence available and the finite list of players on the stage, but we also love the flair of the dramatic outlier, the hero of the story taking the momentus choice that pulls everything together because of his grand act of courage, pulling the baby from the burning building at the last moment. We love to point to the singular moment, the momentus decision. The combination of predictability and momentus choice lets us swing between predictability and heroism; I think we crave both the tragic and heroic story. Unfortunately, I think building a writing practice, career, or love is neither. Ultimately, building love or a writing practice or a new career are more like a series of inexplicabilities combined with a series of small moments of decision. That means heroic acts of determination increase the odds of success, and events provide the necessary but not sufficient coincidence, but the outcome is fundamentally out of our control. What remains for us is whether or not we carry the camera.