Four more holes

I was talking with a friend of mine today about the frustration of being stuck. What do you do? "I'm really not good at moving my ideas past 'stuck,'" he said.

“I feel like other people just choose and then work. I have a river of ideas that I wade in daily. They come rushing at me, swirl and burble around my legs, then go rushing on.

Other people swim down that stream (or are torn from their footing and are swept).

And I just observe and marvel at the beauty of the torrent and wish and lust and never let the water carry me.

I don’t know how to let go of the ground.”

That's the question, in't it? And I thought about my grandfather.

When he was a young man, he played the cello with a symphony orchestra. When he was older, he got a job as a tool and die worker. I always thought it was such a study in contrasts: this man who had played music directed by Shostakovitch, who had this deep love for his craft, had also spent many years happily drilling holes in sheet metal.

And more than that, he talked about them as though they were basically the same thing.

He didn't elevate one over the other. His approach to playing cello was that it was just something you did, it was a job (although it was a really nice one). Sometimes you played the cello in a big room with lots of people. Sometimes you drilled holes in sheet metal.

Creativity and craft is like that. People who are good at their craft don't love it all the time. Sometimes they don't even like it. But they do it; they do it day after day, even when it's not glamorous. Especially when it's not. And I think that being ok with that is one of the essential keys to being really good at anything.

As long as your dream gig is rainbows and unicorns, it will remain unapproachable. Maybe if you looked at it more like it was drilling holes in sheet metal, you'd get over your fantasies about it and realize that it's precisely when it feels like another day drilling holes in sheet metal that you're succeeding at it.

So I told my friend this:

“Every single fabulous motherfucker I’ve ever read from Bukowski to Leonard Cohen says doing their art is horrible and hard and they suck at it and it’s a long slog and takes too long and it’s drilling holes in fucking sheet metal.”

"But why shouldn’t my work be hard?," Cohen said.

“Almost everybody’s work is hard. One is distracted by this notion that there is such a thing as inspiration, that it comes fast and easy. And some people are graced by that style. I’m not. So I have to work as hard as any stiff, to come up with my payload.”

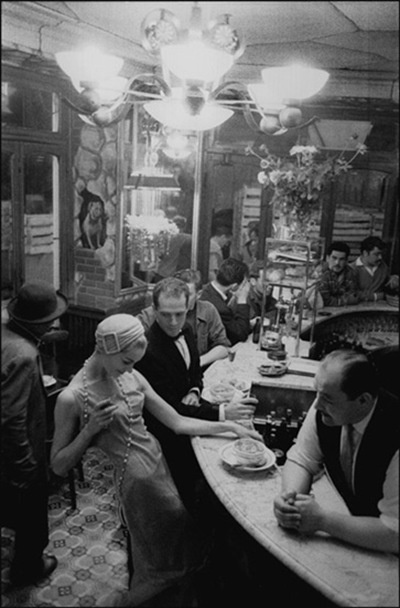

Leonard Cohen, photo by gaët

You can quit tomorrow.

Today, drill four more holes. Grandpa would approve.

The coupling of coincidence and choice

The things that make our lives are so tenuous, so unlikely, that we barely come into being, barely meet the people we’re meant to love, barely find our way in the woods, barely survive catastrophe every day…Trace it far enough and this very moment in your life becomes a rare species, the result of a strange evolution, a butterfly that should already be extinct and survives by the inexplicabilities we call coincidence. The word is often used to mean the accidental but literally means to fall together. The pattern of our lives come from those things that do not drift apart but move together for a little while, like dancers. They come together in these moments that are the coupling of unseen forces, a generative warmth, a secret romance between the unknowns that are also our parents. — Rebecca Solnit

When I started my marathon journey blog, I wrote early on about an observation by Eric Meyer, whose young daughter had passed away. He remarked that after such catastrophes sometimes couples split up, but there is no formula or calculus to know which couples will make it and which won’t. “It isn’t strength that keeps a couple together in the face of crisis. It’s having the luck to remain compatible under the most extreme pressures,” he said. “Like any complex interaction between two complex systems, the outcome is fundamentally unpredictable.” It has to do with the series of moments of coincidence that make up the couple’s history and experience.

Not all the accidents in our lives that provide the things that fall together to make us are secret romances and warmth. Some of the accidents are catastrophes, misfortunes, and several are moments of decision, a moment to change everything and end a marriage, quit one’s job, or move across country. Those moments of decision are patterns and have a regularity, but they are also the results of all the things that barely happened to put us there, at that moment of decision. As Meyer and Solnit note, even these dramatic accidents are not alone sufficient to move a life in one way or another. There is always agency, always a series of moments of decision that give movement to those inexplicable coincidences.

During the process of my separation and divorce a supportive friend once told me her marriage was in shambles and she had been thinking of leaving for a long time, but either she didn’t have the courage or hadn’t yet arrived at the moment of decision to leave. She wasn’t sure why she hadn’t arrived there yet, because she was truly miserable. But the inexplicabilities of her life’s coincidences had taken her to a place that was not her moment of decision. For couples who do split up, the series of accidents and whether and when they lead to a split or not are ultimately unpredictable; frequently friends remark with surprise because the couple in question was one they thought would always hold together.

There is often nothing grand or dramatic or even particularly clear about the arrival of that moment in a marriage; it most often doesn’t arrive with fanfare or drama. Sometimes it arrives because of the accidents of catastrophes and misfortunes and other dramatic moments, but whether or not such catastrophes lead to a moment of decision and what direction that decision takes are fundamentally unpredictable. Rather, they contribute to the coupling of unseen forces of things that did not drift apart, but moved together for a while until that moment of decision was taken up.

Like other incredible events, the exquisite candid and fashion photographs of Frank Horvat often came about because of a coupling of unseen forces, patterns of moments that suddenly coalesced and made manifest a particular moment in time. Horvat’s trick was to carry a camera at all times, so he could increase his chances of capturing such inexplicable coincidences. Building a writing practice or a new career or a new love are all a coupling of coincidence and choice, combined with a decision to carry that camera.

We Americans in particular have a love-hate relationship with the deus ex machina of the story. Like the ancient Greek critics, we prefer for events to unfold neatly based on the statistical evidence available and the finite list of players on the stage, but we also love the flair of the dramatic outlier, the hero of the story taking the momentus choice that pulls everything together because of his grand act of courage, pulling the baby from the burning building at the last moment. We love to point to the singular moment, the momentus decision. The combination of predictability and momentus choice lets us swing between predictability and heroism; I think we crave both the tragic and heroic story. Unfortunately, I think building a writing practice, career, or love is neither. Ultimately, building love or a writing practice or a new career are more like a series of inexplicabilities combined with a series of small moments of decision. That means heroic acts of determination increase the odds of success, and events provide the necessary but not sufficient coincidence, but the outcome is fundamentally out of our control. What remains for us is whether or not we carry the camera.

The next marathon

Marathons are like potato chips, someone said: you can't just do one. It's been true for me; since completing my first marathon last September my mind has been full of planning for my next, and my next after that. To that end, I've managed to successfully maintain a running base through the winter and am heading to Nashville this weekend for a half marathon, which is a stepping stone to my next full marathon (hopefully in June). But that's not the only marathon in my life.

The next big, scary marathon is building my writing practice. Writing is hard, exquisite, terrifying, thrilling for me. I love writing, it's an expansive space I can share and a straitjacket demanding precision and clarity. Most of all, it's a practice that requires building just as a marathon is building miles and having good runs and bad. So, just like I did when I began my marathon journey last year, I've decided to join a group to help develop that practice for myself, Jeff Goins' 500 Words 31 day practice challenge. This blog will be a place where I share my best ideas and writing, a chronicle of my next marathon and a challenge to myself to start where I am in my work and fall down and get up and work again. If you are working to build a practice as a writer, I invite you to check out Jeff's page and consider taking up the challenge yourself. If you do, let me know; I'd love to hear from you.

The next big, scary marathon is building my writing practice. Writing is hard, exquisite, terrifying, thrilling for me. I love writing, it's an expansive space I can share and a straitjacket demanding precision and clarity. Most of all, it's a practice that requires building just as a marathon is building miles and having good runs and bad. So, just like I did when I began my marathon journey last year, I've decided to join a group to help develop that practice for myself, Jeff Goins' 500 Words 31 day practice challenge. This blog will be a place where I share my best ideas and writing, a chronicle of my next marathon and a challenge to myself to start where I am in my work and fall down and get up and work again. If you are working to build a practice as a writer, I invite you to check out Jeff's page and consider taking up the challenge yourself. If you do, let me know; I'd love to hear from you.

Did it! Or, the importance of getting lost

I am a marathoner. It feels so good to be able to say that. They say it will change you (it does), it is an emotionally charged event (it was) and that there's never a good time to do one anyway so you might as well start right now, where you are. So I did. And here we are. Thank you for sharing it with me!

The day was almost perfect in terms of weather; only the last few miles running into a strong wind gave a significant challenge. I fueled well (thank you, Fox Valley Marathon for your excellent course support), and several times was able to just stretch out and lose myself in the midst of some of the midwest's most beautiful scenery. I saw blue heron, snowy egrets, kayaks and canoes, and ran through some stunning wooded areas along the Fox River. This is one of the things people like best about the Fox Valley Marathon (plus, it's relatively flat). It was a "top ten" good day, and my finish time was under 5:30, which was my goal.

The day was almost perfect in terms of weather; only the last few miles running into a strong wind gave a significant challenge. I fueled well (thank you, Fox Valley Marathon for your excellent course support), and several times was able to just stretch out and lose myself in the midst of some of the midwest's most beautiful scenery. I saw blue heron, snowy egrets, kayaks and canoes, and ran through some stunning wooded areas along the Fox River. This is one of the things people like best about the Fox Valley Marathon (plus, it's relatively flat). It was a "top ten" good day, and my finish time was under 5:30, which was my goal.

Out there, I "lost myself" in that positive sense we think of forgetting your troubles, being present where you are, just enjoying things as they come.

This week, I have felt like I am "losing myself" again, only this time it's in the other sense. The post-marathon week has been, for a variety of reasons, emotionally draining, exhausting, just plain hard. My sense of feeling unmoored this week is in stark contrast to the joy and exhilaration of losing myself in the woods on marathon Sunday. One felt like being a leaf floating on a river; the other like a pebble tossed by the waves.

This week, I have felt like I am "losing myself" again, only this time it's in the other sense. The post-marathon week has been, for a variety of reasons, emotionally draining, exhausting, just plain hard. My sense of feeling unmoored this week is in stark contrast to the joy and exhilaration of losing myself in the woods on marathon Sunday. One felt like being a leaf floating on a river; the other like a pebble tossed by the waves.

In both cases I am at a loss for words to describe that "losing myself" feeling. But maybe that's the point. The universe is calling me to lose myself, in both senses of the word, for a while. It's unfamiliar territory.

So, go back to the main lessons I learned from this journey: when you're facing something like that, find some friends or a support network, start where you are, and persist. So that's what I'll do.

Onward.

Running rocks and the merciless blank page

The blank page can be merciless. One of my favorite writers on creativity and performance is Todd Henry, author of Die Empty. In his blog, Todd writes about cultivating the practice of being alone with your thoughts every day.

About fifteen years ago, I heard a friend say that the best practice he’d ever developed was plopping down in a chair first thing in the morning with a notebook and staring at the wall. I thought he was out of his mind until I started doing the same thing. It’s amazing how many thoughts pass through your mind, slipping just beneath the level of your consciousness simply because you aren’t listening for them.

But what do you do when you sit with your thoughts and, well, you don’t have any? What if you reach and There’s. Just. Nothing. There.

Very tempting to give up, to give in to the demands of the day’s busy-ness. For some, mornings are not a quiet, tranquil time to gather thoughts and begin again. They bring anxiety and the bustle of activity, getting kids off to school and not being late for work and remembering the mountain of undone tasks and unmet deadlines.

Celebrate the Habit

One key to making it work is to learn how to enjoy and even celebrate that daily process, regardless of the outcome. Because building the habit itself is useful.

Over time, habit trumps the "monkey mind", creates the structure and space for productive work. A lot of times you can’t see the change. But it’s happening.

Starting a run is a blank page. It can be merciless. There are lots of crappy, just ok, not inspiring at all runs. But they all count. So if you can find a way to enjoy, savor or celebrate each one you will build a habit, and it will stick.

When my teenage son wanted to take up running, I encouraged him to pick up a rock at the end of each run. The rock represented his run for the day. They went into a flower pot on our porch so he could see, over time, the pile growing.

When my teenage son wanted to take up running, I encouraged him to pick up a rock at the end of each run. The rock represented his run for the day. They went into a flower pot on our porch so he could see, over time, the pile growing.

With his usual creativity, he soon took to picking his running rock very seriously – on good days the rocks were smooth and shiny, others were jagged and heavy. It wasn’t too long before he could see a pretty good pile of rocks in the pot. And when the time came for his first 5K, he was ready.

Learn to enjoy the habit, and the habit will become its own reward. The goal isn’t some distant achievement, but the process itself. - Leo Babauta, Zen Habits